When Yale historian Matthew Jacobson created a new website as a way to document the historic inauguration of America’s first black president, he thought the project — then primarily a collection of photographs taken by himself and a few others at President Obama’s inauguration — would be short-lived.

But that moment gave way to others that, in the Yale professor’s view, were both imbued with their own significance and were also “history-in-the-making”: the impact of the 2008 economic collapse, the divisive politics regarding healthcare reform and immigration, the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the rise of such movements as the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street, to name just a few.

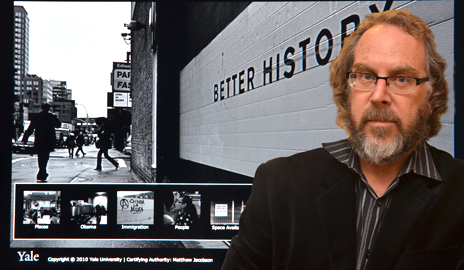

So Jacobson decided to continue his endeavor — called the “Our Better History” project — to capture, as he writes on its website, “the sweeping historical forces at street level.” The name for the project comes from a phrase in Obama’s inaugural address: “The time has come to reaffirm our enduring spirit; to choose our better history ….”

The project’s website, titled “Historian’s Eye,” is now an archive featuring 2,500 of Jacobson’s own photos of recent American events and scenes as well as several hundred by other contributors, plus some 30 hours of the historian’s audiotaped interviews in which citizens across the country — among them unemployed workers, teachers, writers, student activists, artists, and federal judges — share their own personal histories and their insights on American political life.

A professor of American studies, African American studies and history, Jacobson teaches courses on race in U.S. political culture, immigration and migration, and popular culture, among other topics. He uses the site to inspire discussion in his own classes, but he also hopes that “Historian’s Eye” allows his students and other visitors to take in “the current moment” in a different way than they might while watching or listening to the news.

“The momentum of our culture encourages very short memory and very quick judgment,” the Yale faculty member writes on his website. “We take our public discourse mostly in sound bites, and hence things that predate the latest news cycle are most often crowded out of our consideration. ‘Historian’s Eye’ asks you to slow down; to look and listen; to pay close attention and to notice; to entertain a variety of perspectives; to ask varied questions; to think about the current moment as possessing a deep history, and also to think of it as itself historical — futurity’s history. Above all, ‘Historian’s Eye’ asks you to pitch in and talk back.”

Jacobson started his project after being diagnosed with a recurrence of cancer, and says that his illness made him think deeply about his next academic pursuit.

“I thought: Do I really want to rush back to the archive to write my sixth book? Is that the most important thing in the world?” he recalls in an interview. “I decided that I wanted to do academic work but do it in a different register.” His multimedia project allows him to combine his interests in photography and audio.

During the past three years, the historian has traveled to some 30 states, conducting interviews and taking pictures of such common contemporary American scenes as empty storefronts, beleaguered businesses, signage reflective of the recession, and political protests (both by those on the right and on the left). He also posts photographs by other contributors, who have shared images ranging from a Tea Party event in Washington, D.C., to Occupy protests in New York, California and as far away as Korea.

Jacobson says the inspirations for his project, in part, are two long-time chroniclers of American life: the journalist Studs Terkel and photographer Dorothea Lange, both of whom focused on the lives of ordinary people.

“Lange once said that one of the great things about the camera is that it teaches you to see without a camera,” says Jacobson. “While her famous works are really dramatic, many of her images are of the mundane. That kind of gave me courage and loosened me up. Some of my own shots are dramatic, but that isn’t what is important. I am trying to see things — and encourage others to see things — with fresh eyes. I want to build an archive that not only speaks to the moment but also can be a place where whoever is interested can look back years down the line.”

Jacobson acknowledges that some of the people he interviewed — who represent a broad spectrum of professions and geographic areas — might be somewhat less “ordinary” than Terkel’s usual subjects. Among the interviewees featured on his site are a New York City hedge fund manager who reflects on the economic collapse and Jacobson’s Yale colleague Alicia Schmidt Camacho, an American studies professor, who talks about New Haven’s decision to issue ID cards to illegal immigrants in the city. In addition to edited audiotapes, “Historian’s Eye” also features full transcripts of many of Jacobson’s interviews. Visitors are invited to share comments on the interviews and photographs.

People from around the world have also written personally to the Yale faculty member to comment on “Historian’s Eye” and to tell him how much the site resonates with them, he says.

“People remark on how rich it is and how deep it is, and that’s what I wanted,” says Jacobson, whose project has received mention in The New Yorker, among other publications, and has been used by other teachers of history and culture.

He says the project that began with Obama is still very much devoted to his presidency, and what it has meant for America.

“I think the site still tends to be framed by an understanding of Obama’s leadership and the opposition’s behavior,” Jacobson says. “I think whether you are left, right, or center, people recognize that our problems are so big, and there is a lot of despair around that. People are articulating in different ways how hopeless governance has become. We’ve become almost ungovernable. We don’t talk to each other anymore.”

Despite the current political and cultural polarity in America, however, Jacobson says that he believes that the past three years have been a special time in the country.

“It feels like an extraordinary moment of both hope and danger,” he says. “The thing that is interesting is that it seems to feel that way to everybody, whether you are a Tea Partyer or a Wall Street protestor. There’s this feeling that we’re sitting on a razor’s edge, and we are — at any moment — about to deliver our best moment or our worst moment.”

Jacobson notes that — despite the state of the economy and the nation’s divisive politics — the Occupy movement has helped to spur hope for many in the country by beginning a discussion about “the social contract and the ruptures in it.”

“I think the Wall Street protesters have been speaking for a lot of us and saying something important,” he continues. “What has become business-as-usual practices in our country were unheard of a generation ago. In the 1970s a CEO looked at shareholders as one constituency among many that had to be thought about. Now they’re considered the only one. We need to remind ourselves that the practices of much of corporate America should not be taken as business-as-usual.”

Likewise, Jacobson says that while he has observed many Main Streets across America that are full of vacant buildings and people experiencing joblessness and homelessness, he has been uplifted by those he has met on his travels.

“My project has buoyed my optimism in a certain sense,” he says. “I’ve been astonished by the people I’ve met and the people I’ve interviewed along the way. There is an intelligence and humor and resilience to people that I keep seeing, and that makes me feel lucky. Just to have these conversations and to see people refusing to go down makes me hopeful.”

Most importantly, he says, the project has been “life-giving” for him despite his discouragement over the nation’s level of political discourse.

“Even if I was afraid or thought I was dying or that the world was falling apart, the project made me align myself to see beauty,” he says. “I hope the archive reflects that, because aside from being meaningful, I did want to create something that’s beautiful.”